The Music of Anzoro

by Maaike VanderMeer

Mary and I were both doing internships under the guidance of Nyemuse, an AIM missionary who has worked with the ethno arts in East Africa for many years. As we planned the upcoming music composition workshop together, Nyemuse prioritized the most important lessons. This workshop would have to be completed in four days, with half of the teaching time given to a Congolese Pastor who would teach on marriage and family. Nyemuse decided to leave out the lesson on the use of music in spiritual warfare. While I didn’t say anything, I was thinking, “But that sounds so important! I wonder why she doesn’t take out the instrument lesson? I bet it’s going to be a lot more boring than a lesson on spiritual warfare.”

It turns out God and Nyemuse knew better than I. Something unexpected and wonderful came out of that lesson on instruments.

***

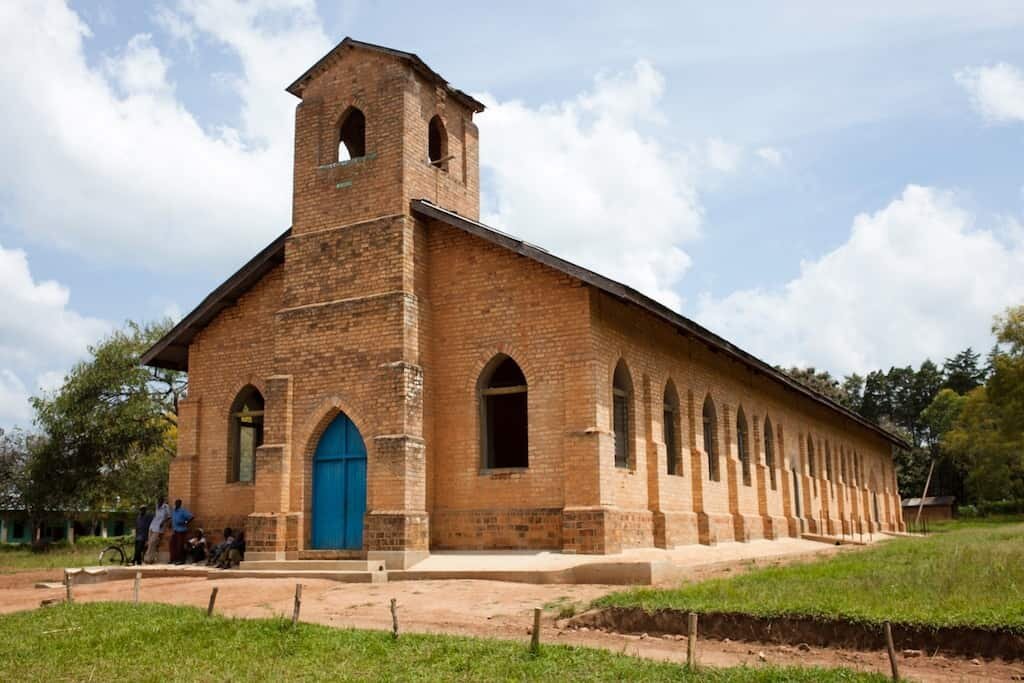

There was an art to writing on this blackboard. It had been set on a rickety table and propped up against one of the thick posts supporting the thatched roof of the church above us. One had to be careful or it would slide right off the table. As Mary asked for names of local instruments, I cautiously filled the blackboard with strange Pazande words. Some of the instruments on the list included drums, shaken instruments, horns, and a xylophone.

“Now,” Mary said, stepping back and pointing to the first word, “What is a drum made of?”

The unanimous response was immediate: “Wood and the skin of an animal.”

“And where does the wood come from?”

“The forest.”

“Who made the trees of the forest?”

“God.”

“And where does the skin come from?”

“From the animal.”

“And who made the animal?”

“God.”

Mary paused, then asked, “So, who does the drum belong too?”

“God!” There is a sound of “aha!” discovery in their voices.

“So when we play it, whose glory should we be playing for?”

“God!”

The lesson continued, and I realized that this was not just a boring classification lesson, but a real application of the Word of God to an important area of their lives that is rarely taught in churches.

Not that it was an ideal time to be teaching it. Many people were already saturated with the high-content lessons they had already heard that morning, and one young lady seated in the first row fell fast asleep. Others were not far behind.

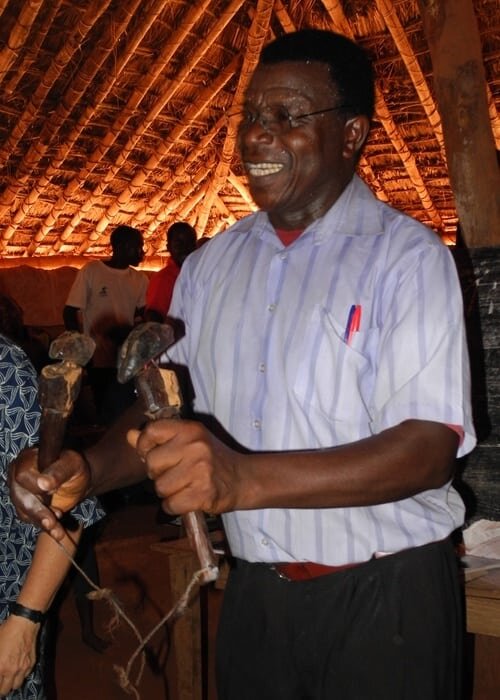

But what we didn’t know was that somewhere in that seemingly inattentive audience, there was one elderly catechist teacher. He had grown up in a family of twenty-four children. When one of his elder brothers died, he inherited as a keepsake a set of instruments that the Zande people call anzoro. Two anzoro are played simultaneously, one with a high pitch and its mate with a low pitch. The handle is crafted from wood, and there is a metal shell fastened to the top, with a small metal ball inside that makes a loud clanging noise. By the time Samuele received these instruments, he was already an active member of the church. Like many of his people, this man associated the anzoro with dancing and drinking parties. Certainly it was not something to be brought to church. So Samuele put the anzoro away out of sight.

But now this lesson! It was something new. When Mary concluded teaching, people dispersed for a thirty minute break. Samuele walked with everyone else along the muddy, red road, past the palm trees and the sleeping goats. The ladies had chai (tea) ready for the seminar attendants, with a little something on the side. But Samuele had something to do besides resting. Something had been hidden in his house for a long time. It was time to bring it out. Samuele knew where he needed to bring it.

***

Fridays were market days. Business was going on with the normal bickering, bartering, and laughter when someone noticed a new sound. Wasn’t that the sound of anzoro? But coming from the church? The day’s business was momentarily forgotten as people hastily left the market, crossed the road, and ran to the mud and wattle church. Some people peeped in the open doorways, others watched over the wall. Inside people were dancing and singing songs of praise to God – and the Pastor was playing anzoro!!

Earlier that day, Samuele had brought his anzoro and his story to church. When people in the audience saw the anzoro, they erupted in loud voices of questions, exclamations, and strong opinions. There were around a dozen pastors present at the workshop who then discussed how best to respond. Together, they agreed that since this set of anzoro had a long, dubious history, there needed to be a prayer of cleansing over it. Some measure of quiet was restored, and a pastor prayed for God’s cleansing and blessing on the anzoro. Then, the hands that had stretched out to ask for blessing, grasped the wooden handles. The church filled with the distinctive music of drums, anzoro, and Christian songs of praise to God in the Zande language. The sound was so loud, so joyful, that the Christians in church jumped out of their seats to dance and sing with all their might. This is what brought the people from the market running.

Traditionally, the anzoro were used to accompany songs of great sadness and great joy. When a chief came to a village, the anzoro and a traditional Zande knife would be held in the same hand. These would be held high and shaken to show honour to the chief. If he was speaking and the people appreciated his words, they would shake their anzoro to show appreciation and honour to his words.

And now, the anzoro was being played in church in the presence of the King of Kings!

Later that day, the pastors talked again and decided that while God’s children could use the anzoro, they would have to make new ones since the set they held had been used in too many places and situations that were not honouring to Christ. Also, they asked that the rhythm and melody used with the anzoro not parallel closely with drinking songs. That same day, they commissioned a local blacksmith to craft a new set of anzoro.

The next day, when the choir of pastors stood to present their new composition, both the old and the new sets of anzoro kept the rhythm. On Sunday, when 1,095 people gathered to a church that would normally seat 300, the President of the churches in that district held up the new set of anzoro and dedicated it to the Lord. I am not a Zande speaker, and all I understood was, “irisa” (praise) and “ziazia, ziazia, ziazia” (“holy, holy, holy”, see Isaiah 6), but it thrilled me to know that Jesus’ lordship was being recognized over all music and instruments in a real way. Something beautiful had been used to worship darkness, but on that hot Sunday morning, it was publicly reclaimed for the worship of the one true God! And all this came from a lesson that I thought would be boring!

Maaike VanderMeer grew up in Africa as a missionary kid and returned in the fall of 2013 to the Democratic Republic of the Congo for a three month internship in the ethnoarts. During those three months, she worked with a group of Congolese to create a radio drama, attended workshops, and recorded and edited Scipture songs in mother tongue languages. Maaike is excited about discipleship through ethnoarts and will study Communications at Moody Bible Institute this year in preparation for long-term work in the Congo. Her vision is that the church of Christ in Congo will be deeply and holistically transformed by the Word of God.